Changemaker Catalyst Award recipient Allison Woolverton interned with Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Baton Rouge during summer of 2017 to study the nuances of immigration law and increase resources for refugee resettlement. Allison is majoring in Political Economy with minors in both Spanish and Social Innovation & Social Entrepreneurship.

When I was three years old and my teacher asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I replied “a freedom-fighter in Afghanistan.” Or, at least, that’s how my parents like to tell the story. I have, though, always felt an incredible desire to try and fix social problems, seek peace in the world, and fight for justice. It sounds obnoxious and very unrealistic, I know. Fortunately, The Taylor Center has shaped my college experience, empowering me with a platform to exercise these ambitions and learn how to, if not change the world, sow the seeds to transform small parts of the community around me. These programs have taught me to believe that, with the right amount of cultural awareness, empathy, and humility, one can and must find sustainable and effective solutions to –at least some of—the problems which riddle society.

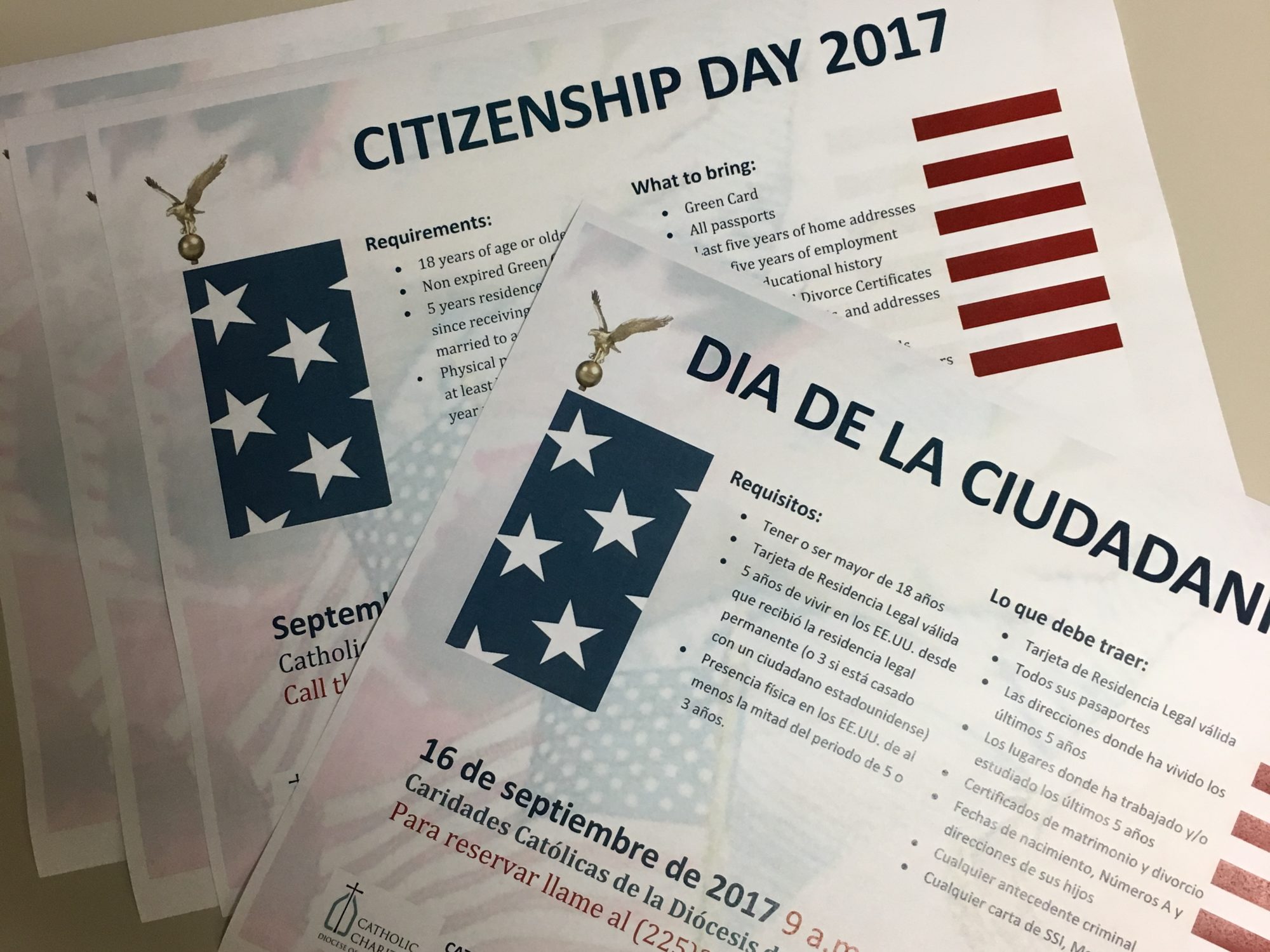

The latest opportunity I have had through the Taylor Center was the chance to intern at Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Baton Rouge by receiving funding through the Changemaker Catalyst Award. I worked in both the Immigration and Refugee Resettlement departments. I spent the first several weeks assisting my supervisors with various tasks, learning how both the refugee resettlement process works and seeing how immigration lawyers help refugees, asylees, and undocumented migrants. I sat in on a cultural orientation session given to newly arrived refugees where I heard the stories of refugees from Turkey, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Cuba. I assisted a women’s entrepreneurship empowerment group, in which refugee women learned to weave traditional Rwandan wall hangings to sell. I assisted an immigration lawyer work through asylum cases by researching the country conditions of refugees seeking admittance. I got to look through a case file to piece together the story of a woman from Honduras who had crossed through the Arizona desert with her baby while fleeing her abusive ex-husband. And just before my internship ended, I had the opportunity to visit dozens of ethnic markets, restaurants and community organizations while distributing information about Citizenship Day, an annual event hosted by Catholic Charities to provide eligible Green Card holders with the materials to apply for citizenship.

Throughout these various projects several things nagged at me, and I wondered if there were not better ways to execute some aspects of the process. For example, when newly arrived refugees attend cultural orientation classes, the well-meaning instructors simply tell them which American cultural norms that they must now abide by without much explanation. It seemed that if one comes from a country where, for example, using physical force to one’s wife is normal, simply saying “by the way you can’t do that here,” would not necessarily ensure that the refugee would understand and abide by American standards of domestic abuse. While distributing Citizenship Day flyers, I wondered if the people we were trying to serve would have adequate transportation to be able to attend the event, as many immigrants live on the outskirts of Baton Rouge, a city with little to no public transportation. I wished that I had more weeks interning to work on addressing some of these concerns.

Throughout my different projects, one experience in particular shaped the way I see my community and my ability to effect change within it. My primary project for the summer was to organize a local Refugee Advisory Council, in imitation of the already existing state-level one. The goal of the council is to connect people from many different sectors of the Baton Rouge community in order share resources and bridge gaps in the refugee resettlement process. Although it seemed intimidating at first, to ask a favor from professionals involved with low-income housing, English as a Second Language, healthcare, or religious organizations, whom I did not know, nearly everyone was extremely enthusiastic and wanted to give their time and efforts to the cause. After several weeks I had organized 17 people on to the council. When the first meeting date finally came around, I was worried that some members might not have much to share or not know what to talk about. However, the meeting proved to be incredibly effective, as people shared moving stories about serving refugees. Several people even shared stories of being a refugee themselves.

Although no concrete “solutions” were laid out at this first meeting, I think everyone walked away touched by the stories shared and inspired with compassion to help refugees in need, whether or not they had thought about the subject at all before. I remember vividly, how enthusiastically members of the committee formed connections with one another, exchanging contact information and excitedly discussing resources they could share. I realized that it was moments like these that bring people to action. When spurring community organization and problem-solving, you have to move people’s hearts before you can change their minds. In that moment I also realized just how important it is, when serving those in need, to share ideas and perspectives with those who we might not normally come in contact with in our areas of study or professions. In just the first meeting of the Baton Rouge Refugee Advisory Council, English teachers met with government workers and lawyers spoke with religious leaders. It is only when we bridge barriers of professional titles and levels of achievement, coming together from all sectors of the city, that an entire community can find solutions.