Changemaker Catalyst Award recipient, Rebecca Wang, traveled to a rural community called Santa Isabel in northwest Ecuador where she worked with Don Adrian Gavilánez at his primary forest refuge, Refugio del Gavilán. During her visit, Rebecca helped Adrian to acquire skills and resources needed for establishing and developing a community-based ecotourism conservation program.

Introduction:

Refugio del Gavilán resides within the Mache Chindul Reserve, which is facing heavy deforestation due to dependency on the cultivation of cash crops such as cacao, corn, and rice to name a few. This area is also a biodiversity hotspot but loss of habitat is threatening many unique species of birds, mammals, amphibians, and reptiles that rely greatly on intact primary forest for survival. Because of a current lack of alternatives, people living in communities within the realm of these tropical forests have little incentive to preserve the forest. Thus, they must rely on cutting down forests in order to clear land for cultivating crops in order to support their families with immediate monetary return. However, in the long-run this system is ultimately NOT sustainable, not for the people in the community or for the species with which they share this ecosystem.

Adrian Gavilanez’s ultimate goal is to establish and manage a sustainable, community-based conservation program by drawing volunteers, students, and tourists to the ecotourism lodge which he hopes to establish at Refugio del Gavilán, a place where people can come to learn more about the natural world and appreciate this biodiversity hotspot. Currently he still lacks many resources and the funding he needs in order to do so and is seeking help and support. With funding thanks to the Changemaker Catalyst Award, Rebecca was able to purchase some resources and supplies for him such as binoculars, headlamps, and field guides that he can use in order to keep practicing the skills he has learned as well as to build his toolbox and expand his library for when future volunteers come visit the Refugio. She helped to train him in biodiversity monitoring skills, such as point-counting methods for bird monitoring and bird identification. She also collaborated with some members from a local non-profit organization to establish the trails for point-counting and record their GPS coordinates so they are ready to use as part of the conservation-based volunteer program they hope to launch this summer.

Below she explains her experience before, during and after the duration of the project, shares what the project accomplished and challenges it met along the way, and talks about where this project is now and where it is going.

Dec 27- Arrival in Quito /Running Errands Pre-Departure

It almost felt surreal to me when I boarded the plane from Fort Lauderdale to Quito, knowing that in almost 5 hours I’d return to a place that I had fallen so deeply in love with the previous semester. It was almost my one-year anniversary from the day I arrived in Quito, shy by just a week. It was only last January 4th, 2017 when my plane landed in the middle of the night for my semester abroad. I remember that I was feeling quite disoriented and lost, as I weaved my way from the terminal to the long line for Customs… where I waited for over an hour; groggy, sleep-deprived, a little nervous and scared; barely coherent in my rusty Spanish speech.

But this time, I felt like I was home. Ironically, I had just left my “real” home, New Orleans, the place I’ve known my entire life since birth, where I grew up, where I went to school, where I now attend college. Yet… I remember feeling the moment the plane landed almost a relief, as if I had been holding my breath in anticipation all this time until the day I could finally back. I guess the months of preparation leading up to this had built up this angst and excitement until when I finally arrived, I could finally breathe again. It was starting, it was happening. I had so much ahead of me still before actually arriving in Refugio del Gavilán to hit the ground running… but all I wanted to do was make it home. Home, where my host mom from my semester abroad was waiting for me. Home, to where the most beautiful mountains I’ve seen in my life were waiting to greet me through the windows of the green bus I would ride to school. Home, to the lush green, the symphony of bird calls resonating throughout the canopy of the tropical dry forest; the humid, warm air wrapping me in its moisture helping my lungs to breathe.

As I daydreamed, I moved quickly through the line… I remember it being a lot longer the last time I was here. In the moment there were only a few people ahead of me and I hadn’t been standing in line for more than 15 minutes.

After retrieving my luggage from the carousel, I scanned the crowd of people for my friend Danny who had come to pick me up from the airport. I saw him standing patiently, with a subtle grin that quickly widened into a huge smile as he opened his arms to embrace me. He brought me to my host mom’s house and helped me to carry my suitcase up the stairs. During the 40-minute car ride I explained to him what I was doing back. As I explained the project to him, I could feel myself getting more excited but I also felt a bit worried.

I hadn’t acquired enough knowledge about amphibians or reptiles, I knew very little about how to go about searching for them much less identifying them. I had made a schedule for what to do each day, but felt underprepared not having any written lesson plans. I hadn’t met the family yet so I was unsure of what to expect. I hadn’t been in direct contact with them. I wasn’t familiar with their schedule yet or what they do on a daily basis. I didn’t know what time commitment they could afford to go out into the field to practice bird ID, protocols or have lessons in English and Ecology or Environmental Biology. But what I did know was that through the months of preparation, I became ever more invested in this project, in getting to know them, in helping them. Their desire to conserve the forest and spread environmental awareness resonated with me and I am devoted to helping them with that cause. My aim for this trip was to first get to know the family and build a relationship with them built on trust and empathy. Along the way I would learn about their personal vision for the future and adapt our plan accordingly in order to accomplish the steps needed to attain each goal as well as lay out future ones.

Despite all the unknowns, I felt optimistic and hopeful and the comfort of being back helped me to feel more at ease. I felt some drowsiness begin to seep in, as I looked through the window, enchanted by the sea full of stars and of city lights glowing from the mountains. As Danny pulled up in front of the apartment gate, I was reawakened by a sudden surge of excitement because soon, I would be reunited with my host mom. I knocked on the little window of the guardroom, and familiar faces greeted me with twinkling eyes as the gate opened. These gentlemen would greet me every day to and from school, “Hooola, ¿cómo te va?” or “¿A dónde vas?” or “Que tengas buen día!” I became so used to seeing them on their different shifts, and seeing them again made me feel at home and really happy.

I had packed a large suitcase, a carryon, and a really stuffed backpack. Inside of the large suitcase I packed a duffel bag that I was planning on using for the commute from Quito to Quininde, knowing that once I arrived there it would be a hassle to try to roll around suitcases through the busy crowded streets. Inside of the large suitcase were also the binoculars, various field guides, and headlamps I was going to bring to Don Gavilanez to start him off with some resources he needs to move forward. We lugged my suitcases up the two flights of stairs where the door had been left ajar by my host mom. When I entered she enveloped me into a tight embrace and we hugged for a while. Then, we chatted with Danny for a short bit until he left to go home. It was really late already, almost 1 AM in the morning, so we agreed to go to bed soon after and see each other in the morning.

I didn’t stay in my original bedroom since my host mom had another student here for a study abroad exchange at USFQ, where I attended while I was here. I settled into the bedroom across my old room, messaged my parents that I had arrived safely, and notified some friends that I was back. Minutes later, I was out like a lamp. It had been such an exhausting day of traveling but I was so glad to be back.

Dec 27 – Day in Quito – Running Errands

Today felt like I was living in a Dora the Explorer episode. I had to get to so many different places to get certain things in preparation for my trip tomorrow to the Refugio del Gavilán. I woke up quite a few hours later than I had planned. My host mom had made some jugo (juice) for me and cut some fruit for me for breakfast. My host sister was there with her daughter, but I barely had any time to spend with them since I had to quickly gather my things and go. I met up with my friend Javier who had enthusiastically agreed to accompany me on all my errands so that we could finally catch up after months of not seeing each other. On our mission today were:

- buy a Claro chip so I could have a functioning phone

- buy rubber boots

- go to Ministerio del Ambiente to pick up Aves del Ecuador, The field guide to the birds of Ecuador

- buy bus tickets from TransEsmeraldas to go to Quininde

The first stop we made was to go to TransEsmeraldas to go to Quininde – we wanted to buy the tickets as early in the day as possible just in case they ran out or we needed to check another bus station. From the bust station, Estación de Río Coca, we took the Ecovia and got off at the stop Baca Ortiz, where we then got off and walked a couple blocks to the office of TransEsmeraldas. Having my friend Javier with me and also having been there for a semester before, brought me this unexpected feeling of familiarity. Normally in situations like these I’d feel so lost, but today, I felt comfortable and confident and driven.

As I was walking, so many familiar scenes brought back memories of days of exploring the city with friends last spring. Taxis zipping through the streets or lined up against the side of the road, their drivers ushering you to take a ride; street vendors grilling plantains, the smoke rising to the roof of their red, yellow, and blue umbrellas, shading them from the heat of the sun beating down. Moms holding their sons’ and daughters’ hands walking with them from school; school children in uniforms and backpacks with cartoon figurines, sharing plastic bags of chochos mixed with salsa and tostados, glass windows of various shops on the streets offering discounts and deals; inviting kiosks serving almuerzo, advertising their lunch menu written in chalk on small blackboards propped up outside. It’s hard to describe the vibe of the city and its streets, the scenery and people bustling about, but all I have to add is that, despite the smell of the diesel in the air and combustion from public buses and taxis…. I felt nostalgic and at home.

We eventually arrived at TransEsmeraldas but the earliest bus ticket being sold was for the next morning at 8 am. I needed something even earlier than that since the commute to Quininde would be 5 hours, and ideally I’d need to arrive well before 1 pm to catch la ranchera (a big truck with rows of benches that take people from the town to the community center) to bring me to La y de la Laguna (the meeting point for all the different communities – I think of it as the community center). Having not found an early departure ticket, Javier and I then had to go to Carcelén, a different bus station, where I was able to purchase a 5:45 AM ticket. Rather than just being an office for one company, Carcelén is one of the main bus stations and is North of Quito (and the one closer to my house). When you enter, it feels like you’re in an airport and a bank at the same time. There are waiting areas with rows of seats, and the walls are lined up with little offices or booths (like in a bank), with glass windows that have an opening at the bottom for you to turn in your bus fare and get a bus ticket back in return from whoever is helping you. In the back are the bus terminals – basically a huge parking lot for the buses, each space has a designated sign with the number of the bus that stations there.

After finally getting my early morning bus ticket, we hopped back on the Ecovia, got off at Manuela Canizares and walked about 6 blocks while resisting the urge to grab tantalizing street food we kept encountering: pan de yucca, arepas, maduros (grilled ripe plantains that are sweet), etc. My friend Luis who works at the Ministerio del Ambiente (Ministery of the Environment) in Quito helped me to purchase a copy of the Ecuador Field Guide of Birds. I had purchased the English version for Don Gavilanez, but I wanted to buy him a Spanish edition of it so that he’d be able to actually read and utilize it. Because you can only purchase it in Ecuador at the Jocotoco Foundation store, I asked Louis to get a copy for me that I’d compensate him for. Having been to Ministerio del Ambiente only once before several months ago, I was really glad to have the company of Javier so that I wouldn’t be lost and alone in the big city and we could navigate the unfamiliar streets together. Finally we arrived, I talked with the security guard and the information desk and Luis’ friend came down with the book, and in return I gave him an envelope with money for the book as well as some face creams Louis asked me to bring back for him from the states. Below are some tools that I was able to bring for Adrian Gavilanez and his Refugio del Gavilán.

Celestron binocs

Two pairs of binoculars donated to Don Adrian for practice identifying birds, training, and future community engagement endeavors and biodiversity monitoring programming

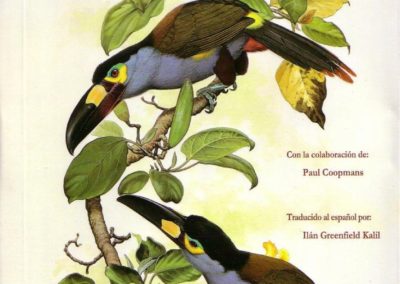

Aves del Ecuador

Spanish Field Guide of the Birds of Ecuador which Don Adrian can practice with and members of the community are able to use when they visit the Refugio del Gavilán in order to learn more about avifauna.

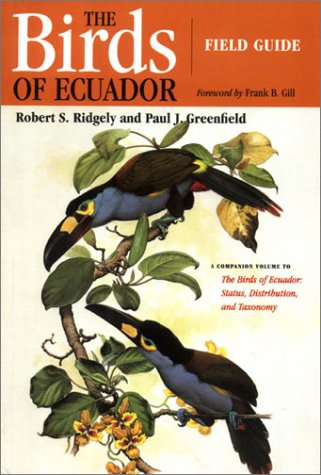

English Version of Birds of Ecuador Field Guide

This will be useful for future volunteers and visitors that come to Refugio del Gavilán

headlamps

Head Lamps necessary for field work and any early morning or evening activities such as surveying for amphibians and reptiles or transect surveys, etc.

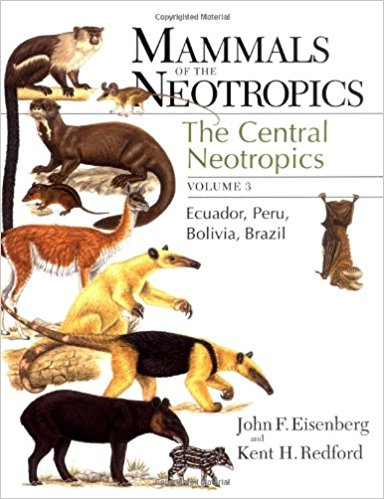

Wildlife of Ecuador

This is a photographic identification field guide. Gabi particularly liked this book for the real-life, captivating photos that make it easy to familiarize oneself with birds, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians of Ecuador.

By this point, we were ravenous for food. We walked around the block to get almuerzo: typically served in three parts – soup, entrée, then dessert, all with juice and usually a salad. We made some videos and took some pictures. I intended to document very step of my experience, but that proved to be difficult and almost impossible later on, once I was at Refugio del Gavilán. However, then, I hadn’t anticipated that and all I knew was that I was gearing up for something potentially life-changing and eye-opening.

Later, we took the trolley back to Estación Río Coca near my house so that we could hop on the green buses from there to go to Cumbayá. Although quite a bit out of our way, I knew that near USFQ campus there was a hardware store (ferretería) where I could get some rubber boots and also a Claro store in the mall adjoining part of the campus where I’d be able to get a phone chip.

Finally after all errands were accomplished, I made it home. My friend Javier rode with me back to Estación Río Coca, even though it was out of his way to go home. It was already 8:30 PM by the time we left, and the sky was dark outside, the mountains were dotted with strings of lights from the urban cities, resembling stars. I was reminded of my bus rides home from USFQ. After a long day of classes followed by hours in a computer lab I wouldn’t leave campus until about 8 pm, and then on my bus ride home, I would gaze out the window, tired but content, comforted by the beauty of the mountain silhouettes dotted with blinking lights. Nostalgia struck again. But I’d soon return home to the warm embrace of my host mom, and then start a long night of packing for my early morning bus ride to Refugio de Gavilán.

Dec 28 – Traveling to Quininde à La Y de la Laguna à Refugio de Gavilán

Before:

How did I prepare for the experience? Thoughts, feelings, steps taken.

Upon first hearing about the project, I didn’t really have a clear idea of what it would entail. I had heard about this opportunity while I was taking a Tropical Field Ecology summer course in Ecuador during which I met a PhD student named Zoe who works with my professor Dr. Karubian. One of the nights that we were at Tapichalaca Reserve, having just finished our days worth mist-netting, data collection, and running stats analyses, we all sat around the dinner table to listen to Zoe take her turn at sharing her life story; how she got to where she was, what her undergraduate experiences were, how she became a PhD student, and what research she is involved in. What really resonated with me was her commitment to helping the community beyond just doing research on the systems within which they exist. She mentioned that she had been working with Don Adrian Gavilanez who owns a primary forest fragment in the Mache Chindul Reserve where only 5% of the Choco rainforest remains. Due to a growing population more of the forest is being cut down, and some community members such as Don Adrian Gavilanez have started to express interest in alternative ways of making money such as ecotourism.

As of now the current situation is that there is very little incentive for people to maintain plots of intact forest. In order to earn money to support their families, community members must depend on growing cacao, corn, rice, plantains and banana, even palm for palm oil. There is only incentive to clear-cut more of the forest and not enough incentive for conservation.

plantains

One example of a cash crop grown popularly in this region as part of subsistence agriculture

“The Great Divide”

I took this picture because it shows such a stark contrast between forest and cleared agricultural landscape.

Travelling by Mule

As you can see, the terrain in this region is rough. When it rains, there are often mudslides, the roads are for the most part, unpaved. Since most people don’t own cars, many people travel by and transport cargo by mule. Gabi was riding on their mule on our way to visit Doña Fanny’s family. I was honored to be invited to come along.

Preparing for my trip over winter break, I met with Zoe and two other students (Caitlin McCormick and Iris Schaitkin) on our team every week to set project goals, set personal deadlines, and give each other feedback on our work. Specifically, each of us was working on sorting through already compiled species lists of common and rare amphibians/reptiles, birds, and mammals to create more succinct field guides highlighting the most prevalent species to be seen. Additionally, we created customized biodiversity-monitoring protocols that are going to be used in the future by volunteers or community members that visit Refugio del Gavilán and that we would teach to Don Adrian Gavilanez as well. I wrote a protocol for point counting of birds, while Caitlin and Iris wrote protocols for herps and mammals. We each created field guides and then Zoe helped us to translate them into Spanish versions as well.

Bird Field Guide I created that Zoe translated into Spanish!

Mammalian Field Guide that Iris created (English Version)

Last, but not least, the Herps Field Guide we created featuring common species.

I later made copies of these materials and compiled them into a binder for Don Gavilanez and made a flexible lesson plan for each day of my stay. Zoe told me that because Adrian has to work in the fields for planting and harvesting crops and also had various other building projects to oversee, most of his mornings would be pretty occupied. She warned me to stay flexible and leave room in the schedule to swap things around, and to be prepared to have some down time. Having not met the family before, I didn’t quite know exactly what to expect.

Part of me felt very nervous – I wanted this to be helpful for Don Gavilanez, I hoped to be a good teacher for him but I also felt a bit insecure about learning the bird species, herps, and mammals myself. However, I was comforted by the fact that we’d be learning together. I was also hoping to teach him some general things about tropical ecology as well provide some context for what we’d see in the field. I was worried about being able to teach in Spanish despite the fact that I lived in Ecuador for 6 months, all my classes had been in Spanish and I taught English at a middle school in Cumbayá. I was worried about not having a big enough vocabulary to use biology or ecology jargon, so I took pictures of relevant pictures of my biology textbook and bookmarked some pages in the pdf version of my General Ecology textbook, and made sure to pack my English-Spanish dictionary.

When I printed a free Herps guide to the Reptiles of the Choco, the scientific names of them didn’t come out legibly – the font was too small and the ink was light gray so I could barely read them without squinting. To readdress this I spent many hours during my layover on my way to Quito as well as on the plane from Fort Lauderdale to Quito, tracing over in black ink all the names of 210 reptiles.

Realizing how much biodiversity of just this taxa left me awestruck and very humbled. I became overwhelmed by curiosity. For some reason, I felt almost an obligation to know all the reptiles, and to know all common bird species or mammal species. I realized I didn’t know enough, and if I didn’t know enough, how did I expect to teach someone about them, or expect an entire community to know about the flora and fauna within the ecosystem they live in?

This mindset can easily stress me out and hold me back, but it helps me to realize the need for effective communication and collaboration within the community. In addition to learning myself, I hoped to, additionally, help raise awareness of the importance of conservation and biodiversity while also catering to the needs of the community members and trying to find a way to do so sustainably. These all seem like really broad and idealistic goals. But I think that starting small is the first step to achieving them. Building relationships with actual community members, focusing efforts on what they need, and developing sustainable ways to achieve goals together to attain a joint vision, I think, is a reliable yet adaptable model to follow.

Another priority we focus on is volunteer recruitment – but it’s progressing slowly and we’ve run into many obstacles. We’ve started an Instagram account (Follow us: refugiodelgavilanec), and we’ve divided up a list of potential volunteer recruitment websites that we’ve signed up for and are monitoring. Sometimes, we find out that we don’t qualify since certain sites don’t allow us to ask volunteers for money. However, for the design of this project – volunteers would be paying to stay at the lodge at Refugio del Gavilán as well as for food – this would be the revenue generated for his family and community.

But, as I mentioned before: small steps. Design Thinking methods have taught me that taking small steps, failing fast, and readjusting goals accordingly is the best way to success. So, for the purpose of my trip, I focused mainly on building trust with Don Gavilanez and his family, working with him and his family directly to assess their needs and understand their goals and vision, then building around empathy to design a step-by-step plan to achieve them. First on the agenda was to get them some materials they’d need – basics, such as some field guides and binoculars, present the protocols and get their feedback to make adjustments accordingly, and practice identifying species of birds, mammals, and/or herps in the field.

Now, onto the real adventures!

After:

I. What did I see and do? What was my impact?

When I arrived in Quininde, I hopped off the bus with my big duffel bag and trudged heavily to the bus stop and awaited the “La Ranchera” (photo below) to take me to La Y de la Laguna (essentially the meeting point for transportation for all of the communities). “La Ranchera” is basically a big transportation truck with rows of benches seating 6-7 people. Getting on one of these things is first come first serve, so as soon as the ranchera pulls up, people start piling on top of one another to grab seats. Words and pictures do not do justice to the scenery we rattled by as we traversed bumpy dirt roads, only some of which had recently been graveled.

Rolling green hills, interspersed with rows of cacao, wide expanses of pasture, peaceful grazing cattle, and wooden houses were also marred by plots of blackened earth, slashed and burnt trees, and smoke. More and more plots like these are being cleared as land for agriculture (below).

Here is a picture of “La Y de la Laguna”, essentially a central meeting point for people of various communities to commute to the nearest town of Quininde, a commercial center for them to run errands, sell their goods, make purchases, buy food, etc. The pick up truck you see is called a “camioneta” – people hop on board with their cargo, and ride to Quininde after disembarking from the “ranchera” or from Quinide back to the communities.

Within 15 minutes of arriving at Refugio del Gavilán, I embarked on a small walk to the edge of the forest surrounding the refuge.

chestnut mandibled toucan

You may be able to see the chestnut tinge on its bill and yellow bib, which are key ID features. The chestnut mandibled toucan looks a lot like the Choco toucan, but its chestnut-washed bill distinguishes it.

I saw a pair of Chestnut mandibled toucans calling alarm calls; loud, resonating, persistent. Rustling leaves and abrupt disturbances amidst the branches brought my attention to furry black howler monkeys, hanging by their tails or foraging on fruit.

If this sounds amazing to you, trust me when I say that each day, that feeling of being utterly awe-struck never faded.

My focus during my trip in the winter was to cultivate and form a personal relationship and deeper bond with Don Gavilanez and his family as well as to gain a better understanding of their background, their day-to-day life, ambitions, and goals.

I worked together with him in developing our naturalist skills in species identification in order to be successful in the implementation of this next step – how to use biodiversity monitoring protocols in order to attract visitors and establish his ecotourism lodge.

I reviewed the protocols with him, and gave some preliminary tutelage on how to use a computer, provided a few English lessons to him and his daughter, introduced him to basic ecological concepts, and practiced bird species identification while becoming more familiar with the trails and fauna within the Refugio. Having spent time with the Gavilanez family, I now have a more complete understanding of their goals and limitations.

I hope that in the future and with more funding, I or others will be able to visit the Refugio again and have the opportunity to bring back more acquired materials he needs to jump-start his venture, which will carry him one step further towards this ultimate goal.

Before I went, I notified members of FCAT, whom I had met during the summer field course, that I would be going. I solicited the assistance of two of my friends, Fernando (FCAT member) and Juana, since they are expert ornithologists with a wealth of experience and knowledge and the advantage of being Ecuadorian natives.

Through the phone app called WhatsApp, I was able to coordinate days and times for my friends at FCAT to visit. Although they had field research to conduct themselves at the Bilsa Biological Research Station, they found time within their busy schedules to help Adrian and I with collecting GPS coordinates of avian point-counting trails as well as the perimeter of one of Adrian’s properties. I am extremely grateful that Beto, Fernando, and Domingo from FCAT, and my friend Juana, were able to help out after I reached out to them!

Point-Count Trail marking

Fernando recoiling the tape measure after marking the 50m distance between our last point-counting stop. We used flagging tape to indicate each 50m stop along the trail Adrian wanted to designate for point-counting.

Fernando indicating to Juana and I where he left the stick to mark the following 50m interval which we’d need to mark with flagging tape.

Sendero 1 Aves 21

Juana and I trailed behind Fernando and Adrian as they marked every 50 m with a stick, and we followed closely to mark each point using orange flagging tape. Here, Juana and I mark point 21 along our 1st trail, labeling it S1Aves21 for “Sendero 1, aves 21”

We made it to the finish line of sendero 1 (trail 1)! Juana and I smile triumphantly after finishing marking this trail! It was very hot and humid, so we were very sweaty. The trail ended in this field or “cancha”. Now, this point-counting trail is established. Later, we will borrow a GPS from Beto, our friend from FCAT, and go with him to take down the GPS coordinates of each point. This data is useful for assessing bird distribution and abundance.

Additionally, they helped us with tree identification and served as mentors to both Adrian and his daughter, Gabi. While we hiked through the trails, they pointed out birds by sound and sight and told us about different species of trees and their uses. Gabi and I each carried around a notebook to record what we were learning. It was truly an informative, engaging, and transforming experience, and one that provides a promising future for collaboration and learning from one another. Here are some photos documenting our journey together:

Gabi explaining to team where to spot bird

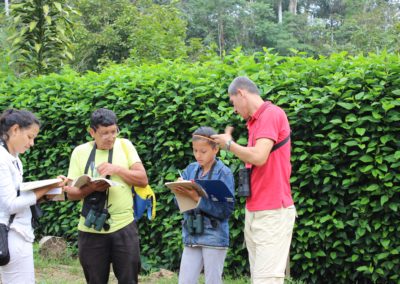

Birders in the field! Practicing their ID skills! Every morning, we would first practice out nearby the cabin (closer to agricultural landscape, more cleared landscape) before going into the forest trails.

Don Gavilanez looking for bird

Domingo and Gabi try to identify the bird that Adrian and Juana are gazing at.

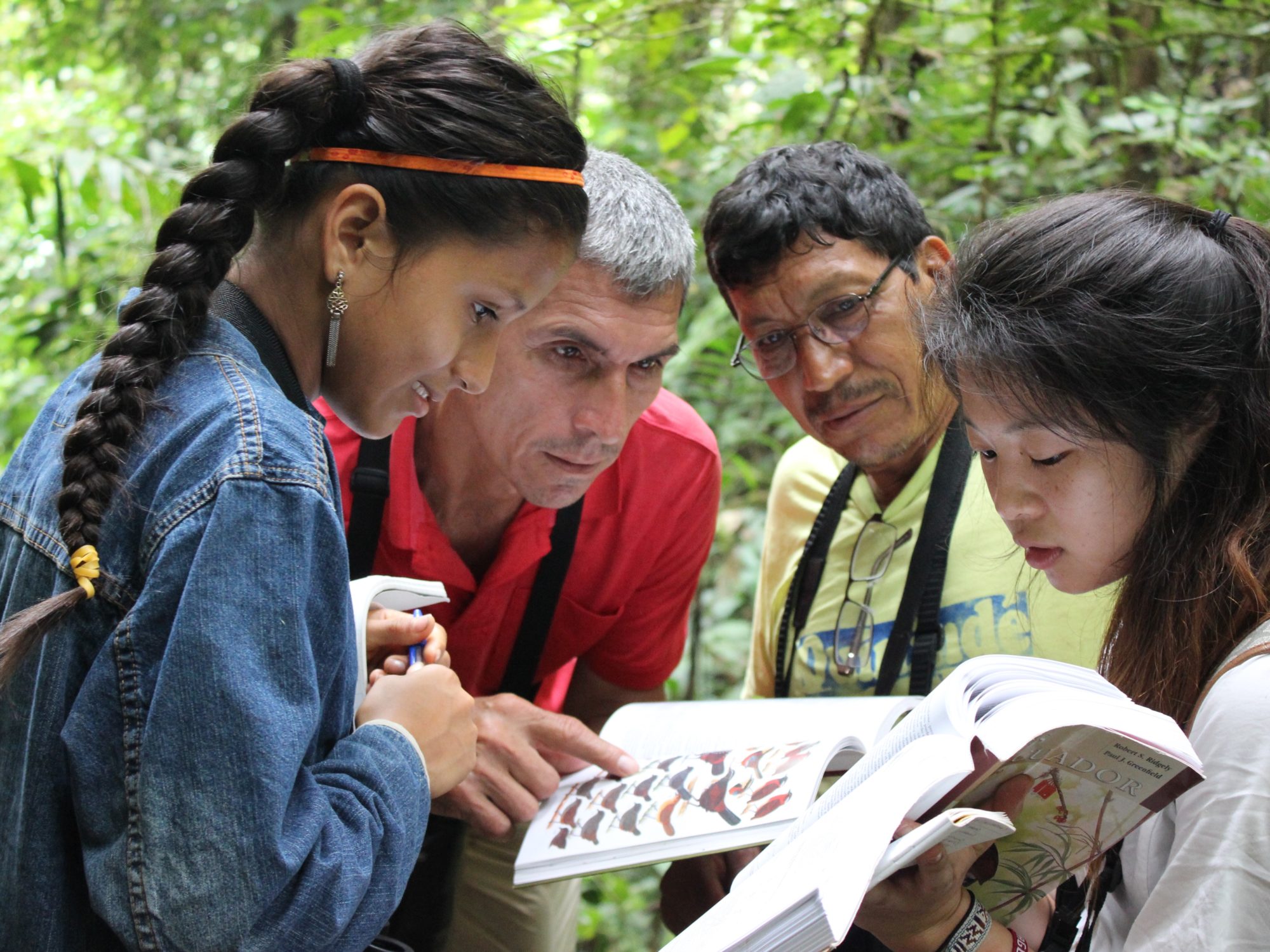

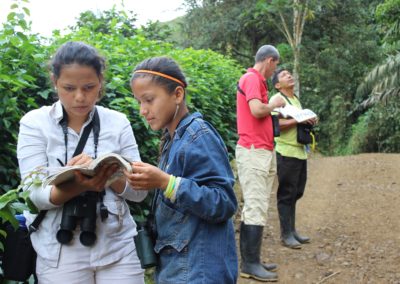

Huddled around closely around the field guide, we tried to identify the bird we saw. The amount of time we spent in the field with Domingo (red shirt) as well as Juana, Fernando, and Beto (not pictured) was invaluable. Adrian, his daughter, Gabi, and myself learned to navigate the field guide, honed our identification skills, and practiced making keen observations about distinguishing bird characteristics. We also learned about different life history strategies of diverse bird species. As pictured, there is a thinner, picture ID book that goes along with the thicker book (bottom) which includes more detailed descriptions and range maps. Bird images and species descriptions are all numbered with corresponding sections and numbers.

Gabi learning

Gabi is writing down point counting identifications and names of trees that Domingo (red shirt) helped us to identify.

note taker Gabi and mentor Juana

During her stay, Juana became a mentor to Gabi and shared her ornithology expertise. Gabi, depicted on the left, is taking notes and documenting bird identifications from our point-counting practice.

Juana’s expertise in ornithology and her familiarity with bird species in NW Ecuador was especially helpful in providing training and guidance to Adrian. I’m glad that upon telling her about this project she was so eager to help out!

Beto, Fernando, Adrian, and Domingo all are helping in this photo to document GPS coordinates of the perimeter of the plot of land that Adrian owns which he wants to reforest.

Here is the team: Left to Right: Beto, Adrian, Gabi, Juana, and Fernando. Back: Doña Fanny

Not pictured, is Fernando, who is taking the photo. This was taken after a long day in the field. Beto brought his GPS so we could record coordinates of the point counting trails we marked a few days before. We also took down coordinates for Adrian’s second plot of land that used to be a cattle pasture. With these coordinates, we hope to be able to generate and create a visitor map. However, we will need to come back to the Refugio del Gavilán and gather coordinates for more trails, the waterfalls, the cabin, etc. to complete the map.

In the video above, Juana explains the difference between the male and female characteristics of a bird species they just witnessed foraging in the field. Juana’s patience and knowledge she shared truly enhanced our learning experience. Adrian and Gabi paid close attention and were actively engaged.

II. What was I Learning?

I learned so much more than just about the local flora and fauna in this Neotropical region. During my stay with Adrian and his family at the Refugio del Gavilán, I gained important insights into their livelihoods within the Mache Chindul Reserve.

I realized my initial lack of knowledge, experience, and understanding about the social and cultural aspects in the region was largely a result of my conservation driven mindset. Although from my conversations with Zoë, I had some ideas about how difficult life was there and how scarce their resources are before my arrival, actually living with them at the Refugio was more revealing and eye opening than anything else.

This speaks to the fact that true understanding comes from real experience. I think that achieving conservation goals cannot be done unless you take time and open your mind to understanding the livelihoods of the people who live in that area and what their socioeconomic needs are. Below, I recount my experience harvesting and selling Salak, the fruit of the Salacca zalacca (Snakeskin Palm), a species native to Indonesia.

Harvesting Salak - Process and Reflections

Through harvesting Salak (Salacca zalacca) with the family and helping them to sell it in town (Quinidé), I realized how labor-intensive, physically demanding, and difficult it is to grow, tend to, and rely on subsistence farming.

Fridays for the Gavilanez family are harvest days. Every Friday, after breakfast we would start harvesting from about 8:30 am until about 1:00 pm, when we would have lunch. Afterwards, we would continue harvesting until we fulfilled the number of buckets requested by his buyers and at least a surplus of two buckets to sell in town the next day.

Trekking through rows and rows of Salak palm (Salacca zalacca), I followed suite as Adrian hacked away at spiny fans of palm leaves. Once we spotted ripened fruits, we would cut our way through thickets of spiny fronds.

Next, we would burrow a long stick into the spiky trunk panels in order to prop open a small entrance just big enough for our hands to reach in to dislodge the fruits from in between the prickly stems lined with thorns.

We would fill satchels and woven baskets with the Salak fruit, and then carry the heavy loads back to the house, where Doña Fanny began to sort the fruit. After harvesting, everyone would help to pour the harvested fruit in batches into a bin. In pairs, we would vigorously shake the bin of fruits in order to get rid of the prickly spines on the fruits through the friction of grinding them against each other. Then, we would pour the de-prickled fruit on a tarp, and help to sort the fruit into ones to sell, ones to feed the animals, and the big riper ones that one lady particularly liked because they burst into cracked smiles.

At the crack of dawn on Saturday mornings, Don Adrian would call for me outside my cabin. 5 AM, still dark outside. He would have already loaded up the mule, with 2 big buckets of Salak on either side, and one he’d carry on his back. We would hike up about half a mile along the inclining muddy trail to the small stop, where the pickup truck would come for us on its way to “La Y de la Laguna” (basically the meet-up point for all the communities to get to town).

Awaiting the Pickup Truck

Doña Fanny waits with Don Gavilanez and Mario for the pickup truck on a Saturday morning to bring us to La Y de la Laguna where we hop off and hop on a ranchera to Quininde, where we’d sell Salak. Since the first truck did not show, Doña Fanny came to accompany us and brought us breakfast, too.

Mario and the Mule

Mario stands with the hardworking mule that helped to carry our tachos (buckets) of Salak up the ascending road leading up to the pickup stop.

Pumped to sell Salak!

Adrian displays his optimism even after the first pickup truck didn’t come for us at 7:30. This sometimes happens on the weekends, as there are few drivers and road conditions may make transportation difficult.

Once there, along with the 10 people also packed in the back of the pick-up truck, we would unload all of our cargo, and reload it on top of the ranchera leaving for 7:30 AM. This ranchera, would take us and about 60 other people to Quininde, where people run errands, sell produce, buy groceries and supplies, and more.

We’d arrive in town by about 9AM and then, on a street corner in front of a supermarket, we would set up shop. On my first Saturday in Quininde, I was completely overwhelmed by all of the bustling activity and the thousands of eyes that I felt scrutinizing me. Adrian told me to jump right in. Two buckets of tantalizing Salak for me to sell. While I held the fort down by this street corner, he carried some in a large bag to sell on foot.

He’d later come back and then stay with me until we sold the rest of the fruit in the two buckets. “Ocho por un dólar! Cuatro por cincuenta centavos! Dos por veinticinco!” I’d call out. At first, I felt self-conscious, a bit timid, and a little scared… I wasn’t familiar with where I was yet and I felt very vulnerable as a foreigner.

As I sat longer, my voice started shaking less, and each time I called out my bargain, I felt more comfortable and more confident. I still felt kind of strange though, kind of like an exotic creature in an exhibit, because people would point, do double takes, come up to me and explicitly ask, “De dónde eres? De dónde vienes?” Where are you from, where did you come from? “Quién conoces?” Who do you know? I started to improvise stories that I thought were simpler, but they often just elicited more questions and more baffled looks.

I tried explaining I was volunteering, that I was here from Quito helping my uncle with harvesting and selling fruit, etc. I realized that I must have been such an enigma. Chinese-looking girl or “chinita” as they endearingly call me, dressed in Western Clothes, speaking Spanish? And, of all places, in Quininde!? I truly felt outside of my own skin, but, one Saturday after the next, I grew more accustomed to this experience. I think people in town maybe got used to seeing this strange girl on the street corner selling Salak, too.

On occasions where Gabi was with us, I always felt great relief in her company. It was nice to have someone to chat with or joke around with on the street corner as we waited for customers to approach our station. Sometimes, she would run off to a nearby food wagon, and purchase a small bag of hard-boiled quail eggs seasoned with salt and pepper for us to share. Moments like these were always special because, although small, it was still a shared and personal experience. As I gradually grew closer to her, I discovered how humble, intelligent, witty, humorous, and even sassy she was.

It was also relieving when Adrian was by my side, because him being there to answer questions from street goers and friends he knew meant I was relieved of my attempts at convincing the world who I was! Adrian typically had a set number of Salak bins set aside for his sister that resided in a different town and a customer from Quito, too, which regularly purchased from him. We would flag down a bicycle cart to help trolley the cargo over to a bus ticket office, where his customers would then go to retrieve the fruit and load it onto their bus from there. All of this required intense physical labor, endurance, patience, and planning. Once that was all done, we’d take a lunch break and then run around town purchasing groceries and needed household items for the family using the proceeds from the harvest.

I am in awe of the grit that people in this region seem to have. From spending time with Adrian, and being with him in the field harvesting, seeing him haul what must be 60-100 lbs of cargo on a 2.5 hour commute to town across 3 vehicles each way – the sheer amount of physical labor he endured already seemed daunting enough. On top of that, it is incredible the motivation and discipline one must possess to wake up at the crack of dawn each day to begin all the day’s tasks: tend to crops, take care of business on the property, put food on the table and cook for a family, support your child through school, pay workers who help you tend the land, raise and provide for farm animals, maintain trails on the property, etc…

These two birds had fell from their nest and are now being taken care of under the wing of Doña Fanny. She feeds them chewed up Salak in this photo, like a mama bird would!

Saltamonte

The Gavilanez mule, Saltamonte, rolls happily in the ground to relax his back muscles after his harness and saddle are taken off after a long day of hauling cargo.

Fulvous Whistling Duck

This Fulvous Whistling Duck apparently had a fall out with two others and when the other two migrated northward, this one stayed behind and has imprinted on Doña Fanny. It loves to nuzzle its bill and head in her warm embrace, and likes to follow Doña Fanny around at all times, getting anxious when she’s not in sight.

Mama Fanny

Pato (duck) and Doña Fanny who takes care of all of the farm animals and is essentially a mother to them all!

Doña Fanny is making her rounds feeding and tending to all the farm animals. Pancho, Gabi’s pet goat, follows. To the right, is the Gavilanez family’s home.

Don Gavilanez leading the way and showing me the trails! The purpose of this tour was for me to document projects he has underway and to communicate what his goals and needs are. He was eager to show that he has initiative to get things done, but needs help with acquiring funds and resources to realize these improvements for the Refugio.

Understanding which tree species are suitable for various ecoservices is an important part of these communities’ relationship with the forest. Adrian shows me how he utilizes his resources to maintain his property at Refugio del Gavilanez. Trail maintenance requires good upkeep and is something that volunteers can help with too!

Some of the prepared wood Adrian has for the new cabin he hopes to build. These pieces of wood would be for constructing the walls of the structure.

Building Material

Don Gavilanez is proudly showing me the good wood he has set aside for building a new couples cabin for future visitors.

Wood for floor boards of new cabin

Don Gavilanez has carefully selected the best wood for each aspect of the cabin.

Don Gavilanez talks with Mario about his job for the day while Mario’s wood-cutting partner works steadily away at the tree trunk in the background. Another responsibility Adrian has is hiring people to help him with projects on his property.

Cascada

There are many waterfalls along the trails of Refugio del Gavilán. In the future, we hope to document where they are located using a GPS, so that with those coordinates we could create a visitor map using GIS. Such waterfalls are only one of the many attractions that visitors can enjoy at Refugio del Gavilán. They also make for good places to look for herps!

Waterfallin’ in LOVE

Here is another waterfall at the Refugio. In the spring/summer, there is a greater volume of water. But in early January, it looks like this.

cacao

Besides tending to the animals, maintaining the property and trails of the Refugio, the Gavilanez family also tends to their crops, such as cacao, to ensure successful harvests.

Escuela de Santa Isabel

This is Gabi’s school. It is the size of about a standard classroom in the US and probably fits at maximum about 30 students.

Harvesting Cacao

Similarly arduous is the process of making chocolate – starting with the harvest of cacao and preparing the beans from the cacao pod to be made into chocolate. Long story short, this process entailed long hours in the hot sun using a machete to hack away weeds and dislodge the fruit from the tree.

With his son Noé, Don Adrian and I basically made an assembly line through the rows of cacao: Don Adrian with his machete cutting down the fruit from the tree, me trailing behind him to pick up the cacao and storing it in the woven basket I carried on my back, and then Noé, using his machete to crack open the shell of the cacao to slide out the slippery, fuzzy-white, cacao beans (with aloe-like texture) into a bucket.

Cacao flowers

Like many tropical fruits, cacao grows directly on the tree bark. Here are the pink flowers preceding the fruit.

Adrian demonstrates why it is worth checking fallen cacao on the ground too for cacao seeds (the part made into chocolate).

Animals that eat the cacao chew away the slimy white fuzzy part outside of the seeds, leaving them cleaned and giving them a head start in the process.

Harvesting cacao is no easy task, you often have to slide down steep hills to get from one tree to several others.

Then, you have to sun-dry the cacao beans, taking advantage of the intermittent windows of time when it wasn’t drizzling or when the clouds parted (if ever).

After sun-drying them, which typically could take up to 2 weeks, you have to stir the cacao beans over a flame in a pot until the skin turned crispy and toasted. After this step, Adrian would pour the toasted batch into a separate metal bowl, and Doña Fanny and I would begin peeling off the flaky toasted layer to reveal a smooth, dark brown, aromatic and warm cacao bean.

what used to be white/fuzzy skin around the cacao is now a paper-thin skin, similar to what is on roasted peanuts. This is what we peel off to get to the cacao nibs!

Then we had to little by little funnel it through this metal compartment that we’d attach to the edge of a table, and use a handle to churn the cacao beans into a creamy chocolate paste. To watch the process of making chocolate, watch this video below:

These experiences only provide a small glimpse of what life is like for the Gavilanez family (and probably for many other families like theirs in the community of Santa Isabel as well as other communities). The purpose of me sharing these vignettes with you is merely to portray their relationship and close proximity with the forest, their dependence on agriculture, and generally speaking, what occupies their lives and their time. When thinking about conservation, it is crucial to have an understanding of a community’s culture, values, priorities, livelihoods, their economy, resources, and their needs. In the grand scheme of things, my visit at Refugio del Gavilanez, which was only about 16 days (4 of those days were spent traveling/gearing up) is relatively short. However, during this short amount of time, these experiences I shared with them as well as our conversations had a profound impact on my understanding and perspectives regarding community-based conservation.

III. How was Don Gavilanez learning and what were his reflections?

Don Gavilanez (Adrian) picked up on some English phrases I taught him, mainly ones that he could apply directly and those he could remember how to use in context. Among several of them, some were “eat quickly”, “Can I have some water, please?”, and his favorite “Thank you, honey”, which he loved to use with Doña Fanny at each meal to thank her for cooking for us. Needless to say, Doña Fanny also loved hearing it, as she would always laugh, shaking her head with a big smile brimming ear to ear.

I realized that he learned best through practice, application, and repetitive usage. Although I gave him about 4 structured English lessons highlighting vocabulary and basic grammatical structure (present vs. past tense and present progressive), it seemed more effective to teach him exact phrases that he could use daily or specific things he wanted to say.

He also was able to practice bird identification skills and learned how to navigate the field guide. With the help of Juana and fellow FCAT members Fernando, Domingo, and Beto, Don Adrian gained more confidence in identifying birds by distinguishing characteristics and bird songs and calls, and also learned the scientific names of common ones. The more time we spent in the field and the more he gained hands-on experience, he was able to recognize species more rapidly. He became better at identifying distinguishing characteristics as well as articulating them.

One of the first few days I was there, I generated some questions to survey what Don Gavilanez already knew and how he envisioned a volunteer program within an ecotourism framework would be like. Below are the questions I asked him and his responses in Spanish.

¿Qué más quiere conocer acerca de las aves? (What more do you wish to know about the birds?)

Conocer más sobre los técnicos de conservación y las causas por las cuales están en peligro de extinción. Para de esta manera ayudar de manera más eficiente al medioambiente.

Knowing more about the methods of conservation and the causes for why they are in danger of extinction as a way to more efficiently help the environment.

¿Haga una lista de las aves que ya conoce usted y una pequeña descripción sobre su apariencia y sus hábitos y alimenticios? (Make a list of the birds you know about and a small description about their behavior and food resources.)

- Tucanes – pico de unos 15 cm, colores rojo, amarillo, negro, y comen semillas y frutas. Toucans with bills of about 15 cm, red, yellow, and black in color; eat seeds and fruits.

- Pavas- se alimentan de chapil, pambil; su color es gris- opaco. La cabeza y los patas son rojos y tienen un tamaño de unos 25 o 30 cm. Turkeys -eating palm fruits; of opaque gray color; head and feet red; body size 25-30 cm.

- Perdizones – pasan a nivel del suelo; ponen huevos de color celeste con puntitos cafes; comen insectos durante la mañana y al atardecer. forages on the ground; lays blue eggs with brown spots; eats insects during the day and at sunset/dusk

- Corraleras – andan siempre en grupo; el macho es más grande y de color café-oscuro. La mayoría del tiempo pasan a nivel del suelo. forage in groups; the male is bigger and cafe-colored; spends most of the time foraging on the ground

- Palomas – Su alimentación se basa en semillas; elaboran sus nidos no muy altos. Existen varias especies pero sus colores casi siempre varian entre plomo café y blanco – food source mainly seeds; makes nests very high up in trees; has many species of varied colors ranging from brown to white.

- Loras – su alimentación es muy variada de semillas y frutos del bosque; son de tamaño y colores bastantes diferentes entre una especie y otra. Parrots – varied diet of seeds and forest fruits; size and color of birds are widely variable especially from one species to the next.

- Los caciques – son de color negro, café, y blanco; andan en grupo; sus nidos son muy llamativos ya que miren hasta un metro de largo; su dieta se basa en frutos y semillas – Cacique birds primarily black, brown or white in color; forage in groups; tear-shaped nests hanging from tree branches are very distinct and are visible from a meter away; fruit and seed-based diet

- Las chirrocas – no son fáciles de observar ya que su especie se encuentra amenazada; su hábitat se encuentran no muy alto en medio de entre el suelo buscoso y los copas de los arboles ; son de color amarillo con negro – are very easy to observe even though the species is threatened; preferred habitat is intermediate in between the ground and tree tops nestled in the heart of the trees. Yellow and black in color.

¿ Cómo se imagina un programa para voluntarios en el futuro? ¿Cuál es su objetivo con el monitoreo de la biodiversidad presente en el refugio? ¿ Cómo es el itinerario y las actividades a realizarse?

(How do you imagine a volunteer program in the future? What would be your objective in the monitoring of biodiversity present in the Refugio? What would the schedule and activities be like in reality?)

Lo ideal sería que un voluntario disfrute el bosque y del hospedaje que ofrecemos y puedan participar en las actividades diarias que se realizan en el refugio: se pueden realizar la cosecha de los árboles frutales, los voluntarios también pueden disfrutar del avistamiento de aves y si lo desean pueden realizar estudios y análisis de todas las especies de flora y fauna presentes en la propiedad. Acerca de monitoreo desearía que cada vez sea más frecuente y se pueda plasmar con evidencia real que es lo que se está logrando y ver los avances en la conservación de las especies que habitan en toda esa región.

Ideally, the volunteer would enjoy the forest and the hospitality that we offer them and could participate in daily activities in the refugio: they can participate in the harvest of tree-growing fruits. The volunteers can also enjoy bird sightings and if they wish, accomplish studies and analyses on all the flora and fauna present on this property. In regards to monitoring, I wish for it to each time be with more frequency and that real evidence captures what is being achieved and makes apparent/visible the conservation advances for the species that live in all of this region.

What was expected vs. unexpected?

I learned more about how people live in the community just by being there and participating in their daily activities. For example, every Friday morning after breakfast we would go out to harvest a fruit called Salak, which we would then sort later into buckets and plastic bins that we would bring, on Saturdays, all the way to the nearest town (hub of all commercial activity), Quininde. On harvest day, Don Gavilanez would strap the buckets of Salak on to their mule to move it to the top of the hill where the camioneta (a pick up truck) would stop by to pick us up in the morning to bring us to La Y de la Laguna where the Ranchera would take us to Quininde. Both commutes are between an hour or hour and a half so taking part in this every Friday, Saturday and Sunday made me realize how difficult and inconvenient life is there.

While we were in Quininde, after selling the fruit on the streets, we would also go to run errands and buy groceries, which we would then put into the now emptied plastic bins to transport it back home with us. With the money that we would make selling the fruit, we would buy groceries, school supplies, or other necessities. Since people rely on commercial cultivation of crops like corn, rice, cacao (among others) for subsistence, everyone has to work long hours in the field tending to the crops, find ways to pay helpers, and maintain their farms (feeding different farm animals, herding cows, treating animal wounds, etc.).

I also learned that people work very hard to make ends meet and nothing comes easily. The water that we used at home and in the cabin I stayed in came from a 2500 L tank that is channeled through tubes to wherever it is needed. There is a switch on the tank where you can turn the water supply on or off – so people try to conserve it as much as they can. Here in the states, I feel like we take water for granted and it’s available everywhere and all we do is turn on the faucet and it comes pouring out. There, everyone is more mindful of water scarcity and tries to use it only when absolutely necessary.

Another thing that made me really perceive things differently is access to education and quality of education. I knew going into the experience that the level of education in these communities wsd not high and that culturally, a higher prioritization is placed on beginning a family at a young age. Since I come from a culturally different background growing up in the states and being of an immigrant family, this experience helped me to realize that access to education is a privilege that not everyone can afford. For me, it was always understood that pursuit of education came first. I always knew without a doubt that after high school I would go to college, and after college I would go on to pursue an advanced degree, such as a masters and eventually a PhD. I bolster my academics with lab experience and field experience – in this epoch of my life goals are very academics-centric. What is perhaps symptomatic of many millennials of my generation is that career-driven mindset fostered by increasingly competitive admissions into professional/graduate schools and a job market that continues to raise the bar. As a result, I myself place starting my own family last on my priority list. Because I am preoccupied constantly about how to stay afloat in school, much less take care of myself and my responsibilities and maintain relationships with friends and family, I simply do not have much more mental energy nor do I feel the need to think about getting married/having kids/starting a family.

Cultural differences and values aside, other discrepancies I noticed between our livelihoods and theirs include affordability of education, access to resources/funding,and standard of living.

To go to Tulane, I have to pay about 10K every semester, which somehow my parents are finding a way to meet with the help of student loans. However, for some kids in the community of Santa Isabel – a futile 30-minute walk to school only for the teacher not to show up is a common experience that happens frequently. Beyond that, those who can afford to go to high school sometimes don’t have the means to go to university even if they have the desire to go and specialize in something. Don Gavilanez’s son, for example, told me that he isn’t in university because a semester costs $2000 and he can’t afford that and doesn’t have that money to sustain a college education for longer than one semester. That conversation became a pivotal moment that solidified the realization of how lucky and how privileged I am to be able to afford a college education. I am also lucky in that, as part of a college institution, I have the opportunity to apply for grants that support extracurricular activities to enrich my academic experience. In line with that, is my enhanced ability to then use these opportunities and resources to achieve conservation goals. It is much easier for me, than someone from Santa Isabel, to apply for and receive grant funds as a student and pay for airplane tickets to bring me to places of conservation need, an opportunity that benefits me experience-wise. It is much easier for me, than it is for someone in Santa Isabel (or another similar community) to make sustainable life choices such as banning straws, or recycling, or only buying ‘fair trade certified’ products, or not personally cutting down trees to grow food to survive on.

Reflecting upon my standard of living along with my status and position societally and globally, in comparison to those of people like Adrian Gavilanez, left me with a sense of a shocking distinction. In addition, the difference in our reliance on and relationship with nature was felt more profoundly than I could have ever anticipated before.

I believe that such experiences are crucial to nourishing a deeper understanding and greater empathy for livelihoods and landscapes other than our own. I hope that these anecdotes and reflections of mine will inspire readers to seek out opportunities to learn actively about other cultures, livelihoods, and our environmental impact beyond just our immediate surroundings. Let’s begin by thinking about the broader impacts of our fields, our work, our beliefs and how they interconnect and overlap with others. We can make an impact by becoming more informed through open-minded learning, connecting with people through meaningful interactions, and being proactive by taking action one step at a time.

IV. What’s Next? How can we best help Don Gavilanez, what are his needs, and how can we help him to achieve this? What are we doing about it, what work is in progress?

During my stay, I sat down with Don Adrian, Doña Fanny, and his son, Noé to talk about improvements to amenities that they wanted to make down the line. Already, Adrian has started preparing the lumber necessary to build another small couples cabin. However, he lacks sufficient funds to acquire the necessary materials. We created a detailed spreadsheet of the supplies he would need, wrote down estimated costs, and then went to town to verify them with vendors in Quininde and identify good potential stores to do business with. By applying for grants, we may be able to help fund this aspect of the project which is to improve the amenities at the Refugio to better suit the needs of visitors/volunteers that come and to further enhance their experience. Right now, though, our focus is to help integrate Refugio del Gavilán in its already established community by designing programs to engage other local community members to be a part of this larger conservation effort. We also hope that our programs will attract both national and international volunteers to Refugio del Gavilán and provide an enriching experience for them as well such that both volunteers and the community of Santa Isabel are benefiting from an intercultural exchange focused on conservation, education, and progress.

Right now, Rachel Cook, a Master’s Student in Jordan Karubian’s lab, is continuing work on a different segment of this project focused on community engagement. Together, she and I meet weekly with Zoe and Caitilin McCormick (senior majoring in EEB) to continue grant writing and designing program activities that we hope to test out Summer 2019. Our educational programming includes both environmental lesson plans and English as a Second Language lesson plans. Together, we hope to secure more grant funding to enable us to acquire supplies and materials to realize the programming activities. We also are continuing our work on volunteer recruitment as well. We hope to be approved by a volunteer recruitment website called Omprakosh which largely emphasizes the need for community engagement in volunteer opportunities. Since Adrian mentioned his desire to welcome more community members to the Refugio to learn about his initiative, we have designed an Open House schedule with potential activities for community members visiting the Refugio. The hope is that future volunteers can test-run this Open House schedule with the feedback of Adrian and community members so that we can tailor it accordingly to their interests!

My friends Nicole Funk and Salomé Izurieta (Ecuadorian native) went to the Refugio, as well, last summer (2018). I asked them to create video testimonials of their experiences there, as well, which can be found on our YouTube Channel that I created for Refugio del Gavilán (see video below).

Our ongoing project goals include: Programming to foster more community engagement and attract more volunteers, creating resources for establishing phenology trails (trees) at the Refugio as requested by Adrian, and more funding for purchasing supplies like GPS units and camera traps for biodiversity monitoring. In addition, we hope to to find financial support for purchasing educational materials like bilingual storybooks, and grammar books to help inspire concrete lesson plans. We also continue work on volunteer recruitment through social media outlets and presentations on campus.

To get involved, please contact me and Zoe Diaz-Martin at zdiazmar@tulane.edu.

Thanks for following this adventure! 🙂 We are only just beginning.

Instagram: refugiodelgavilanec

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCr_3eP78EM3QM2eG4ivVaZg

Email: refugiodelgavilanec@gmail.com